Recommended Resources

Thursday 15 December 2011

Strategies for Challenging Christmas Situations

Christmas can be very difficult for children. This article focuses on three challenging areas families face during Christmas: giving and receiving gifts, managing Christmas excitement, and understanding routine changes.

1. Gift Giving and Receiving – The excitement of getting gifts can be overwhelming for children. Help them understand polite giving and receiving of gifts with these strategies.

Involve Children in Giving – Let children help pick out and wrap gifts. By participating in the gift giving process, children become interested in seeing other people’s reaction to the gift. Even young children can choose between two gifts, put a bow or tape on the wrapping paper, and decide where the gift should go under the tree.

Practice Receiving – Role play receiving a gift and thanking someone for it. Make writing thank you cards part of your family routine so children understand how to thank people politely for presents.

2. Christmas Energy – Christmas events often mean sweet foods and late bedtimes. Use the strategies below to manage energy levels and make bedtime successful.

Keep Children Active – Sledging, walking, and playing games outside during the day can help children use their energy in a healthy and positive way. Keep children active during the day so they will be tired at night making bedtime easier.

Limit Sweets – Sweet, biscuits and fizzy pop are prevalent during Christmas. These foods are high in sugar and caffeine. They cause children to be overly active and make falling asleep difficult. Set rules about how much and when these foods can be consumed and provide healthy alternatives.

Stay on a Sleep Routine – Even when children are not in school, a consistent sleep routine is important. Have children wake up and go to bed at a regular time. Plan morning events such as Christmas shopping to motivate children to wake up and get ready for the day.

3. Christmas Routine Changes – Many children benefit from consistent routines and have difficulty with change. Make Christmas routine changes less stressful with these simple tips.

Use Visuals – Have a Christmas calendar that lists events in writing, drawing, or picture format depending on the child’s level. Refer to the calendar to prepare children for the day’s events and help them understand what is going on and when.

Involve Children – Let children add new events to the calendar. If there are important events the family must attend, explain why attending is important. If there are events that are debatable, include children’s input in decisions about attending the event.

Friday 2 December 2011

Data Protection? Child Protection?

Please find below a real email conversation between a Parent and a Head Teacher. It begs the question; Where will it all end?

Please note, any personal data has been removed (irony discuss). We welcome your views.

> Good morning,

> I've just phoned asking if my children could have a class list each as they are planning a little party, also they will soon be writing Christmas cards. I was told that it couldn't be done due to data protection. What data? We know all this information anyway. We just don't want to miss anybody out. Obviously [child in reception] in particular is likely to forget quite a few.

>

> Please tell me this is a mistake. We ask every year and have never been refused before. As I said, there is no data required, just a list of names.

>

> Thank you

>

> Mr YYY

> Good morning Mr YYY,

>

> I am sorry however we will not be giving out class lists. We do not publish class lists in line with school policy which has been reviewed. Some parents do not want their child's information passed on and we also cannot guarantee how information will be used or disposed of.

>

> I am sure you will understand that we have to take every step to ensure the safety of our children and that information is held and used in line with data protection.

>

> Kind regards

>

> Mrs Xxx

>

Dear Mrs Xxx,

I'm sorry, I'm honestly not trying to be difficult, I just don't understand.

I understand that child protection and data protection issues are crucially important. I also understand that people do not like their private details being passed on, although I find it difficult to believe that parents do not want their children's names to be known. What I don't understand is that this is information we already have. All the children know each other's names. Indeed, as a parent of three children at Unnamed School, I know a large amount of children's names. In addition to this, a teacher will, as part of their twice daily routine and legal requirements take a register using the children's names. If we work hard enough on this at home we can compile a Christmas card list and party invitation list from our collective memories.

I'm not asking you to change your mind, we can manage party invitations and Christmas cards by ourselves. However, I would like to make it clear that we do not require any sensitive information, or indeed any information that isn't given out by teachers twice a day to the other children. In fact, we didn't even need surnames.

This is a ludicrously over protective policy which serves only to further the division between school and families and create a lack of community ethos. I have been into assemblies in your school and heard you refer to yourselves as a family. This policy is neither family or community friendly. One has to ask where will this end, should we remove names from coat pegs, perhaps we should blur out the faces on class photos and school website images, perhaps we could give the children numbers instead of names. I note with interest that the school newsletter now only uses first names and initial surname letter (unless of course it is the y4 boys). Perhaps, in line with what appears to be your school policy you could supply a list of names in this format so that children are not overlooked. Incidentally, the school newsletter lacks identity and has no feeling of personality.

My request was intended to save us a little time, ironically it has achieved the exact opposite. More importantly however, it was intended to ensure that we included all the children in our children's classes.

Wishing you very best wishes

Mr YYY

Wednesday 23 November 2011

Effective Communication between Home and School: Ideas for Parents and Professionals

Parents, teachers, and support staff all have the same goal, a child’s learning, but sometimes communication breakdowns cause inefficiency and disagreement in accomplishing this goal. This article includes ideas for establishing communication systems to make this the best and most effective year yet.

1. Communicate Early – Communicate early either in written form or through a conversation at the beginning of the school year. Early communication sets the stage for year long collaboration by establishing a system and setting expectations.

Professionals – Let parents know classroom expectations, schedules, important dates, and contact information for other professionals working with their child. A classroom information sheet with a handwritten note is a friendly way to start the year.

Parents – Be sure you provide current records and updated information (e.g. phone number and email address) to teachers and therapists. Include any other important information in a letter or email so the professional can refer to it during the year.

2. Have a Consistent System – Establish a communication system that works for both professionals and families. Some people communicate well over email while others like to have printed information in a folder or notebook. Discuss which method works best and stick with it. Providing information back and forth is important for consistency across environments. Use communication systems to discuss how strategies are working and what changes might be helpful.

Professionals – For regular communication use a format that is accessible to all families. For example, have a newsletter or regularly updated website. Include an area in the newsletter for handwritten child-specific comments. Another idea for smaller classrooms is to have daily notes or a journal to send back and forth between school and home. Communication encourages a running dialogue and often results in new information that can translate into effective classroom results.

Parents – Keep professionals up to date about home progress as well as any physical (e.g. child isn’t sleeping well) or emotional (e.g. a pet passed away) changes at home. Often times a child’s personal experiences affect their behaviour and academics. Use the teacher’s preferred communication method (email, note, phone) so they receive the information in a timely fashion.

3. Be Positive – Notes, phone calls, and emails frequently are used for negative rather than positive communication. This can create a situation where parents and professionals prefer not to hear from each other. Keep positive news part of updates. Be sure to highlight progress in difficult areas and note when the child is making progress on a skill. Compliment the other person’s hard work and note when a child is accomplishing goals due to work in other environments.

4. Understand Limitations – People balance professional and personal lives and it is important to respect their time. Busy professionals want updates and information on children, but parents should recognise professionals work with many children. Parents want to work on skills with their child, but they may be busy, need additional resources, or not clearly understand why something is being done. Communicate, have patience, and remember everyone has the same goal.

1. Communicate Early – Communicate early either in written form or through a conversation at the beginning of the school year. Early communication sets the stage for year long collaboration by establishing a system and setting expectations.

Professionals – Let parents know classroom expectations, schedules, important dates, and contact information for other professionals working with their child. A classroom information sheet with a handwritten note is a friendly way to start the year.

Parents – Be sure you provide current records and updated information (e.g. phone number and email address) to teachers and therapists. Include any other important information in a letter or email so the professional can refer to it during the year.

2. Have a Consistent System – Establish a communication system that works for both professionals and families. Some people communicate well over email while others like to have printed information in a folder or notebook. Discuss which method works best and stick with it. Providing information back and forth is important for consistency across environments. Use communication systems to discuss how strategies are working and what changes might be helpful.

Professionals – For regular communication use a format that is accessible to all families. For example, have a newsletter or regularly updated website. Include an area in the newsletter for handwritten child-specific comments. Another idea for smaller classrooms is to have daily notes or a journal to send back and forth between school and home. Communication encourages a running dialogue and often results in new information that can translate into effective classroom results.

Parents – Keep professionals up to date about home progress as well as any physical (e.g. child isn’t sleeping well) or emotional (e.g. a pet passed away) changes at home. Often times a child’s personal experiences affect their behaviour and academics. Use the teacher’s preferred communication method (email, note, phone) so they receive the information in a timely fashion.

3. Be Positive – Notes, phone calls, and emails frequently are used for negative rather than positive communication. This can create a situation where parents and professionals prefer not to hear from each other. Keep positive news part of updates. Be sure to highlight progress in difficult areas and note when the child is making progress on a skill. Compliment the other person’s hard work and note when a child is accomplishing goals due to work in other environments.

4. Understand Limitations – People balance professional and personal lives and it is important to respect their time. Busy professionals want updates and information on children, but parents should recognise professionals work with many children. Parents want to work on skills with their child, but they may be busy, need additional resources, or not clearly understand why something is being done. Communicate, have patience, and remember everyone has the same goal.

Monday 21 November 2011

Ways to Make Day Trips Less Stressful

Set expectations - Be sure to let children know what to expect. Clearly tell them, “We are going to the doctor. We will wait in the office and then Dr. Smith will see you. I will be with you if you are afraid or have any questions.” If you are doing more than one thing, let the child know, “We are going to the supermarket, the post office, and then the park.”

Provide support for the child to be successful - Some children benefit from having information in writing or in a drawing format. Reading stories in advance that discuss what is going to happen can reduce anxiety. Images from stories including social Stories provide a way for children to see what is expected of them. Use illustrations and/or words during an event to reassure children.

Involve children in planning the day - Often children are told what to do and have little ownership in decisions. Letting children make a few choices in an outing helps them feel they are a part of the process. For example, let the child pick which errand the family does first.

Praise children for a job well done - As you go through the day, be sure to reinforce children for listening, following directions, and being kind to others. This shows children they get more attention for following the rules and routines than for breaking them.

Update children regarding timetable changes - Schedule changes are likely to happen on a regular basis. When changes occur, let children know what the change is and how it will affect their plans. For example, “James, the library is not open. We will still go to Aunt Jen’s but we will go to the library tomorrow.”

Plan for delays - Rarely do things go exactly as planned. Prepare for basic concerns such as hunger, boredom, and delays by packing snacks and portable activities like games or books. Make sure to have a back up plan if restaurants or shops are busy.

Let children be involved - Children are less likely to break rules if they are busy. When you are shopping get the children to help you locate items. If you are in the doctor’s surgery get the child to help you fill out the forms by eliciting their responses to simple questions like name, address, etc.

Be consistent - If you create a reward system where the child earns something for doing X, Y, and Z or a promise is made for the child to get something after going to the shops, be consistent. If you say, “You get to play your game when we get home if ….” be sure to reinforce them only if they actually accomplished their goal. When children are given mixed messages about rewards, the inconsistency can lead them to expect rewards when they have not met their end of the deal. Although it may be difficult at first, children will quickly learn you mean what you say if you hold your ground.

Thursday 17 November 2011

Promoting Positive Behaviour

People First Education are pleased to announce a one off event in Birmingham:

Promoting Positive Behaviour

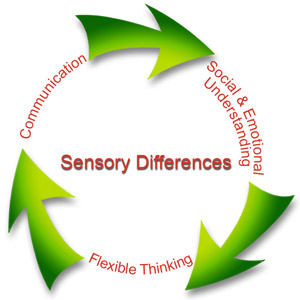

Promoting Positive behaviour for learners with a range of needs including Autism, Asperger Syndrome and ADHD:

A day course for educators and/or support staff, designed to enable successful inclusion of individuals and groups whilst fully meeting the needs of their peers.

The day will include:

• An overview of how the impairments affecting learners with Autistic Spectrum Disorders and/or ADHD may cause them to behave negatively.

• An examination of the root causes and triggers behind negative behaviour and how to avoid them.

• Strategies and interventions for adapting the sensory environment to meet the behavioural needs of learners with Autistic Spectrum Disorders and/or ADHD.

• A range of strategies for promoting positive behaviour through effective practice.

• Attendees are encouraged to bring inclusion questions and points for discussion.

Venue and date:

Thursday 19th January 2012

Holiday Inn Express, Lionel Street,

Birmingham B3 1JE

9:15 am – 3:30 pm

Dyslexia Training Dates for 2012

Tuesday 10th January 2012

Toby carvery, Nottingham Road, Chaddesden,

Derby, DE21 6LZ

Thursday 12th January 2012

Holiday Inn, London Road, Ipswich, IP2 0UA

Friday 13th January 2012

Holiday Inn Express, Norwich Sports Village, Drayton High Rd, Norwich, NR6 5DU

Tuesday 17th January 2012

Leicester Stage Hotel,

Leicester Rd, Wigston Fields, Leicester, LE18 1JW

Wednesday 18th January 2012

Beeches Hotel, Wilford Lane,

West Bridgford Nottingham NG2 7RN

Friday 20th January 2012

Premier Inn, The Haymarket, Bristol,

BS1 3LR

Tuesday 24th January 2012

Holiday Inn Express, Vicar Lane, Bradford BD1 5LD

Thursday 26th January 2012

Holiday Inn Express

Danestrete, Stevenage, Herts SG1 1XB

Friday 27th January 2012

Holiday Inn, Caton Rd, Lancaster, LA1 3RA

Monday 30th January 2012

Novotel, 4 Whitehall Quay, Leeds, LS1 4HR

Tuesday 31st January 2012

Holiday Inn Express, Wilstead Rd,

Elstow, Bedford, MK42 9BF

Thursday 2nd February 2011

Holiday Inn,

Canterbury Road, Ashford, TN24 8QQ

Friday 3rd February 2012

Holiday Inn Express, M65 Jct 10 Burnley, BB12 0TJ

Monday 6th February 2012

Fairfield Hall

Fairfield, Park Lane, Croydon CR9 1DG

Tuesday 7th February 2012

Winchester Royal Hotel, St Peter St, Winchester

SO23 8BS

To book on any of these events click on the sunflower below right

Wednesday 9 November 2011

Helping Children Cope with Stressful Situations

Children can feel stress at home or school and it can take a toll on them. Help children learn to reduce and cope with stress by using these strategies.

1. Identify Causes - If the cause of the stress isn’t easily identifiable, keep a journal and write down times when the child is anxious or upset to determine patterns. Are there sleepless nights before a spelling test? Do they look anxious before going on the playground? Use these patterns to pinpoint the activities and situations that may be stressful for the child.

2. Discuss or Write About the Situation – Once you identify what is causing the stress, discuss or help children write about why it is stressful. For example, if they are stressed before every spelling test, they may fear getting a bad result or feeling helpless. Write a list of things they can do to be proactive and reduce stress. In this example, they can practice more, ask the teacher if they have a question, or know they are trying their best. Developing proactive strategies is a way to feel more in control of the situation and reduce stress. Some situations will always be stressful, but often children think about the worst-case scenario rather than a realistic consequence. Children also may not realize other people also find the situation stressful. By discussing their feelings, the most likely outcome of the situation, and the fact that other people also experience stress, children’s fears and feelings of loneliness may be decreased. Additionally, the simple act of talking or writing about something stressful or scary can help children feel better.

3. Reduce Opportunities for Stress – Some stressful situations are avoidable. For example, if football practice is stressful for a child because they don’t enjoy the game and aren’t very good at it, find another activity that is a better fit with their interests and abilities.

4. Find Ways to Relieve Stress – People of all ages feel stress and learning to cope with it in a positive way is a lifelong lesson. When a situation is stressful, sometimes taking a break is helpful. Give children a place to go and collect their thoughts before returning to the group. Teach them to say, “I need a time out,’ or ‘Please give me a minute.’ Use physical fitness as a way to channel energy in a positive manner. Taking a walk, running, jumping, or playing catch can help children release tension and stress. If a child can’t leave the setting, a stress ball is an easy to carry tool.

5. Prepare Children for New Situations – Often new situations are stressful for children. Read stories, write about, and discuss upcoming events to prepare children and set expectations. Encourage them to ask questions and let them know how a new event or change will affect them. Preparing for activities in advance can make the situation easier such as visiting a new school or sending a letter to the aunt and uncle they will visit.

Tuesday 1 November 2011

Fun Feelings Activities

Recognising your own feelings and identifying the feelings of others are foundation skills for developing more involved social skills such as learning to cope with feelings and responding appropriately to the feelings of others.

1. Provide Multiple Examples: Feelings can be difficult to teach because they are expressed in a variety of settings, have many synonyms, and involve understanding subtle clues. In order to teach identification of emotions, provide examples in different settings through stories, pictures, videos, real-life experiences, and role play.

2. Show Feelings are Important: Children need to understand that it is alright to talk about and express feelings. Demonstrate this by asking children how they feel, sharing your feelings, and discussing how you cope with your feelings and respond to the feelings of others.

3. Use Natural Opportunities: When reading, watching movies, or in real-world situations, look for opportunities to discuss feelings. If the child is upset, use this as an opportunity to teach appropriate responses and coping strategies. For example, “Trevor, I know you are angry that you have to leave the playground. Take 3 deep breaths to calm your body then join the class in line.” If another child is upset demonstrate how to handle the situation. For example, “Malcolm is upset. Let’s see if we can help him.”

4. Set Time Aside to Practice: Just as maths and reading require practice so do social skills. Take a few minutes during the day to work on social skills. Since children may be overwhelmed by feelings it is important to practice expressing and responding to feelings when they are calm.

Role Play: Below are a few games that include role play of emotions.

Get children to select a feelings word or emotions card and act out the feeling on the card.

Let children select a feelings word or card and role play when they felt this way.

Put children in pairs. Have one child pick a feeling and act it out. The other child responds to the first child’s feelings.

Discuss Feelings: Show children pictures or drawings of facial expressions or scenes demonstrating feelings. Ask the following questions:

How does the character feel?

How do you know how the character feels? For example, they are smiling/frowning.

When have you felt this way?

What would you do if a friend felt this way?

What do you do when you feel this way?

Use Art and Literacy: The arts provide a different way to think about feelings. They allow children to see the details of specific emotions and experience the look and feel of the emotion through a different medium. Art activities include:

Have children draw a facial expression or scene showing a feeling.

Have children write a story about a time they felt a certain way and what they did about it.

Create a feelings book. On each page have a drawing of a feeling and a short sentence, “I feel sad/happy/scared when….” Keep each child’s book in the literacy center.

Focus on a feeling by having a book specifically about the feeling that includes when the child feels this way and what coping strategies to use for managing the emotion.

Thursday 13 October 2011

Preparing Children for Trick or Treating

Dressing up to go trick or treating is very exciting for children and it creates lasting memories for both children and parents. Help children prepare for trick or treating with these five strategies.

1. Select a Costume – Help children select a costume that fits properly and is safe. Children may be uncomfortable with anything on their face especially make up. Some children may not like masks because of sensory issues or limited vision. Keep these factors in mind when selecting an outfit. For children who have difficulties with masks, holding a mask rather than wearing it or not using one at all may make the evening more enjoyable.

2. Set Costume Guidelines – Children often want to wear their costume other times than trick or treating. Let them know if/when they can wear it besides trick or treating. Be sure to tell them this before they buy the costume and after it is purchased. Explain why they can wear the costume only at certain times. For example, “You can put it on in the evening for a few minutes to see how you look, but you can only wear it for a little while so it doesn’t get dirty before Halloween.”

3. Practice Going to People’s Doors – Role play going to someone’s door, saying “Trick or treat,” holding a bag out, and saying “Thank you.” Remind children to be polite, wait their turn, and take only one piece of candy when they are asked to select something. It is tempting to rush to a door and take a handful of things when offered a basket or bowl to select from so multiple opportunities for review are important. Be sure to practice other things that may happen such as someone not being home or someone complimenting them on their costume.

4. Establish Guidelines in Advance – Prepare children for factors such as: What time trick or treating starts and ends; How they know when it ends; Where they can trick or treat (e.g. only houses with lights on, only people the child knows, only homes in a four street radius, etc.); and What the rules are such as staying with a sibling or parent. Be sure to review these guidelines days in advance with a story, visual cards, or written rules. Before trick or treating, review them again so children clearly understand expectations.

5. Set Sweet Guidelines– Children become very excited about getting sweets and other treats while trick or treating. Set rules in advance about eating sweets. Let children know before trick or treating that they need to bring all of the sweets back for you to check before they can eat it. Make sure children have dinner before trick or treating so they are not hungry. Have guidelines about the number of pieces they can eat per day and create a schedule for when they can eat their sweets. Display the sweets plan where they can easily look if they have questions.

Thursday 6 October 2011

Correction: New Dates for ADHD, ASD, Dyslexia and Dyspraxia Training

Please note, yesterday's update comtained errors. Please find below the correct dates and titles:

Dyslexia:

5th December 2011:

Gateshead

6th December 2011:

Sheffield

7th December 2011:

Sutton Colefield

8th December 2011:

Huddersfield

9th December 2011:

Cheltenham

12th December 2011:

Oxford

13th December 2011:

Hull

14th December 2011:

Hartlepool

Social Story:

29th November 2011

Manchester

30th November 2011

Liverpool

1st December 2011

Ellesmere Port, Cheshire

ADHD:

11th October 2011 Bristol

Autism Day Course:

17th October 2011

Burnley

18th October 2011

Birmingham

Wednesday 28 September 2011

Teaching Conversational Skills

Conversational skills build a foundation for developing friendships, cooperating with other people, and communicating effectively with people in every aspect of life. Although the art of conversation is difficult to address, below are some strategies for teaching basic conversational skills.

1. Model Skills – Children learn from watching other people and then practicing skills. Role play is a fun and extremely effective way to teach skills because it lets children learn from examples. During role play model an appropriate greeting or conversation. Let children see how questions are asked and answered and how people remain on topic. Keep the ‘skits’ short and simple at first to establish the basic skills then expand on them later.

2. Practice Small Steps - Just like any other skill, social skills need to be broken into smaller steps and practiced repeatedly. Role play greetings by teaching the child to say, “Hello” and then expand to, “Hello, how are you?”

3. Multiple Phrases, Settings, and People – Conversational skills should be developed with a variety of people, phrases, and novel settings. To promote generalization of skills, introduce different questions and wording when role playing such as: “Good morning,” “Hello,” and “Hi there!” By doing this, children learn there are various greetings and responses. Since conversations occur throughout the day with different people, recruit people in the school or community to help the child practice. Ask the crossing guard or librarian to engage the child in a conversation that incorporates the skills being practiced.

4. Remember Body Language – When practicing conversational skills, be sure to include key skills such as personal space (approximately an arm’s length is considered appropriate in the United States), body language, and facial cues. These unspoken aspects of conversation are often extremely difficult for children to grasp and should be included in role play and instruction.

5. Ways to Reduce Repetition – Children frequently learn saying hello or asking someone their name is part of a conversation, so they may repeatedly incorporate these phrases in the same conversation. One way to practice saying something only once is to hold up a finger as a visual cue during role play. For example, if there is a question or phrase that should only be used once, hold up a finger during conversational practice time. After the child asks the question put your finger down. This is a cue that the child already has asked the question. After the child has used this cue successfully a number of times, practice without the visual cue and then praise them for remembering to ask the question only once. Another strategy is to have the child keep a hand (preferably the left hand if you are teaching them to shake hands) in their pocket with one finger pointed. After they ask their favorite question, have them stop pointing or stop pointing and remove their hand from their pocket. This allows the child to remind themselves they used this phrase or question and other people are not able to see this personal cue.

6. Praise and Review - Praise children for greeting people, using a phrase once, or ending a conversation appropriately. Often it is best to praise children during role play or after the child is away from other people to avoid embarrassing them. To reinforce the skill, be sure to review what they did correctly. For example, “I like the way you asked Mr. James if he was having a nice day only once.” If a novel situation occurs naturally, role play it later and use it as a learning experience.

Wednesday 14 September 2011

Teaching Young People to Understand and Respond to Feelings

Children often struggle not only with understanding their feelings, but also relating to other people’s feelings. These skills are critical for personal well being and building relationships. This article includes steps for teaching children to understand and manage their feelings as well as identify and respond to other people’s feelings.

1. Identifying Feelings – Teach children to recognise when they have a specific feeling. Whether happy, sad, or angry the first step in coping with a feeling is identifying it. Help children identify feelings by discussing emotions when they occur. If a child is angry say, “I see you are angry. You have your arms crossed and are stomping your feet.” Another tool is to role play times when specific emotions surface. Use novel examples as well as recent experiences for the child. Discuss and write about different feelings in a feelings journal. Use the journal to write about events and the emotions, responses, and consequences the events elicited.

2. Planning for Strong Feelings – Help children cope with intense feelings by creating coping strategies. Have a quiet place for children to take a break when angry or sad. Give children tools and teach them how and when to use them such as a stress ball or a trampoline. These tools help children release energy in a positive way. Encourage children to use words or write about their feelings. Establish a phrase the child can use to remove themselves from stressful or upsetting situations. The phrase gives children a way to politely excuse themselves, regain control, and then return to the situation. Select a short phrase that can be used in a variety of situations such as, “Excuse me. I need a minute to think.”

3. Recognising Other People’s Feelings – Learning to empathize with other people and respond appropriately to another person’s feelings, is an important skill for building relationships. Show pictures and drawings or role play situations to discuss the words, body language, and experiences that indicate a person’s feelings. When discussing a child’s own feelings, incorporate the concept that peers and adults have similar feelings in the same situation. This helps children develop empathy. Read stories where characters experience events that are happy, sad, surprising, or frustrating. Discuss why the characters felt the way they did and what they said or did to indicate their feelings.

4. Responding to Other People’s Feelings – Not only do children have to identify other people’s feelings, but they also need to learn how to respond when someone is angry, sad, or excited. Teach children appropriate responses through role play and reviewing past events. Discuss how different people in the role play feel, how their body language and words show their feelings, and the best response for the situation. Also discuss how the child would feel if this happened to them and how they would like other people to respond. This helps children learn to empathize with other people.

Thursday 8 September 2011

Mother 'prescribes' coffee to counter the effects of seven-year-old son's ADHD

It's more usually regarded as a morning pick-me-up, but coffee may help to calm attention deficit hyperactivity disorder sufferers down.

A mother of a hyperactive son believes the hot drink counters his symptoms and now carefully 'prescribes' it to her young son.

Christie Haskel turned to the internet after noticing that her son, Rowan, displayed some of the classic signs of ADHD.

Cup of Joe: Coffee may calm ADHD sufferers, believes Christie Haskel who says it has helped calm her son's hyperactivity

'At home there was a lot of hyperactivity,' the mother told ABC News.

She said Rowan, seven, was 'not able to keep his hands to himself, talking when he's not supposed to talk,' and lacked 'concentration or ability to concentrate when he needed to.'

Online, she found a host of information suggesting that the drink's caffeine content may help Rowan and allow him to avoid the side-effects of ADHD drugs such as Ritalin.

She now gives him two 4-ounce mugs of milky coffee a day, at precise intervals and with a rigorous dedication that is normally given to prescription drugs.

No silver bullet: Though Ms Haskel remains sanguine about the drink's effects, she says it is worth a try for those who may wish to avoid drugs such as Ritalin

And, unlike some medicines, the experience of drinking a cup of coffee is certainly no hardship. 'It tastes good and it calms me down' Rowan told the news channel.

Ms Haskel is pleased with the encouraging results and has blogged her story on CafeMom.com's The Stir.

'If we ask him to sit down and do homework, he can actually do it'

'He doesn't overreact if we ask him to pick up Legos, rather than screaming and throwing himself on the floor.

'And if we ask him to sit down and do homework, he can actually do it,' she said to ABC News.

However, some scientists and doctors warn against self-diagnosis and prescribing caffeine as a sedative.

Dr. Richard Besser, senior health and medical editor for ABC News, said: 'A lot of children get into trouble by treatments that are just designed by parents who find stuff on the Internet.'

There is a danger, too, that some parents may see caffeine as the answer to what may be a more severe problem - and the added risk that coffee may solve one problem but create other medical issues in its path.

Though not approved as a treatment of ADHD, coffee may be more than just a morning ritual

Known - and well documented - side-effects of caffeine include increased heart rate, sleeplessness, anxiety attacks and mood changes.

Dr. David Rosenberg, chief of psychiatry at the Children's Hospital of Michigan in Detroit told ABC News: 'Caffeine is not the answer for real, bona fide ADHD.

'I don't want parents to be diluted into a false sense of security that if I just go to the local Starbucks, I'm going to cure my son or daughter's ADHD.'

New research shows nearly one in 10 American children now receive an ADHD diagnosis - a number that is firmly increasing, according to the U.S. Center for Disease Control and Prevention.

Dr. Lara J. Akinbami, an author of the study told the channel that 'ADHD continues to increase, and that has implications for educational and health care because kids with ADHD disproportionately use more services, and there are several co-morbid conditions that go along with it.'

Christie Haskel remains loyal to the wonder drink, though, and says that it is worth giving a chance.

A mother of a hyperactive son believes the hot drink counters his symptoms and now carefully 'prescribes' it to her young son.

Christie Haskel turned to the internet after noticing that her son, Rowan, displayed some of the classic signs of ADHD.

Cup of Joe: Coffee may calm ADHD sufferers, believes Christie Haskel who says it has helped calm her son's hyperactivity

'At home there was a lot of hyperactivity,' the mother told ABC News.

She said Rowan, seven, was 'not able to keep his hands to himself, talking when he's not supposed to talk,' and lacked 'concentration or ability to concentrate when he needed to.'

Online, she found a host of information suggesting that the drink's caffeine content may help Rowan and allow him to avoid the side-effects of ADHD drugs such as Ritalin.

She now gives him two 4-ounce mugs of milky coffee a day, at precise intervals and with a rigorous dedication that is normally given to prescription drugs.

No silver bullet: Though Ms Haskel remains sanguine about the drink's effects, she says it is worth a try for those who may wish to avoid drugs such as Ritalin

And, unlike some medicines, the experience of drinking a cup of coffee is certainly no hardship. 'It tastes good and it calms me down' Rowan told the news channel.

Ms Haskel is pleased with the encouraging results and has blogged her story on CafeMom.com's The Stir.

'If we ask him to sit down and do homework, he can actually do it'

'He doesn't overreact if we ask him to pick up Legos, rather than screaming and throwing himself on the floor.

'And if we ask him to sit down and do homework, he can actually do it,' she said to ABC News.

However, some scientists and doctors warn against self-diagnosis and prescribing caffeine as a sedative.

Dr. Richard Besser, senior health and medical editor for ABC News, said: 'A lot of children get into trouble by treatments that are just designed by parents who find stuff on the Internet.'

There is a danger, too, that some parents may see caffeine as the answer to what may be a more severe problem - and the added risk that coffee may solve one problem but create other medical issues in its path.

Though not approved as a treatment of ADHD, coffee may be more than just a morning ritual

Known - and well documented - side-effects of caffeine include increased heart rate, sleeplessness, anxiety attacks and mood changes.

Dr. David Rosenberg, chief of psychiatry at the Children's Hospital of Michigan in Detroit told ABC News: 'Caffeine is not the answer for real, bona fide ADHD.

'I don't want parents to be diluted into a false sense of security that if I just go to the local Starbucks, I'm going to cure my son or daughter's ADHD.'

New research shows nearly one in 10 American children now receive an ADHD diagnosis - a number that is firmly increasing, according to the U.S. Center for Disease Control and Prevention.

Dr. Lara J. Akinbami, an author of the study told the channel that 'ADHD continues to increase, and that has implications for educational and health care because kids with ADHD disproportionately use more services, and there are several co-morbid conditions that go along with it.'

Christie Haskel remains loyal to the wonder drink, though, and says that it is worth giving a chance.

Wednesday 7 September 2011

Strategies for Developing Classroom Friendships

Children spend a significant amount of time in the classroom which is a wonderful environment to build lasting friendships. This article includes strategies for helping children develop friendships with classmates.

1. Activities – Create situations where children collaborate and work together. Look at their interests and abilities and use paired or group activities to encourage interaction. Physical activities like team sports or throwing a ball and counting the number of times it remains in the air before being dropped are fun and require teamwork. Small group projects like creating a collage where children have assigned roles such as writer, picture locator, and materials cutter, help children focus on a task and interact to complete it. Depending on a child’s age and ability, give them more or less structured directions. For older children, let them select different roles and problem solve how to complete the project as a way to learn collaboration and compromise.

2. Direct Instruction – Sometimes it is necessary to discuss and outline social skills clearly for children to understand them. Role plays and group discussions about meeting someone new, having a conversation, sharing, helping, and being a good sport can illustrate aspects of the skills children may overlook. Rehearse new scenarios, frequent interactions, or a past event to practice real-world situations. Start by clearly explaining the specific actions in the skill. For example, when practicing having a conversation discuss and practice greetings, responding to questions, asking questions, attending to the person, and saying good-bye. Have children role play a scene with the skill. Discuss possible things to say and do when having a conversation and how choices during a conversation affect the outcome of the interaction.

3. Bridge Home and School – Parents and teachers can work together to promote an interest in school friendships. Have children write a story about their classroom friends then ask parents to read and discuss the story at home. For younger children, include information about friends in notes home. Mention things like, “Alex played cars with Sarah in the sandbox.” Encourage parents to ask about who the child played with or worked with at school.

4. Activities Outside the Classroom - Children often see classmates at community activities. Joining a new activity with a classmate is a way to encourage friendships outside of school and have the support of an existing friend at a new event. Whether playing on a baseball team or attending story time, participating with someone the child knows is a way for them to have additional common interests.

5. Don’t Pressure Children – Teaching children the basics of being good to peers is important. Sometimes children develop close friendships this way, other times they will remain classmates. Do not force a friendship, but encourage children to share, say kind things, and be good to their classmates. Use children’s interests to involve them in activities such as sports, clubs, or neighborhood get-togethers they enjoy, so they continue to participate and find friends with similar hobbies.

1. Activities – Create situations where children collaborate and work together. Look at their interests and abilities and use paired or group activities to encourage interaction. Physical activities like team sports or throwing a ball and counting the number of times it remains in the air before being dropped are fun and require teamwork. Small group projects like creating a collage where children have assigned roles such as writer, picture locator, and materials cutter, help children focus on a task and interact to complete it. Depending on a child’s age and ability, give them more or less structured directions. For older children, let them select different roles and problem solve how to complete the project as a way to learn collaboration and compromise.

2. Direct Instruction – Sometimes it is necessary to discuss and outline social skills clearly for children to understand them. Role plays and group discussions about meeting someone new, having a conversation, sharing, helping, and being a good sport can illustrate aspects of the skills children may overlook. Rehearse new scenarios, frequent interactions, or a past event to practice real-world situations. Start by clearly explaining the specific actions in the skill. For example, when practicing having a conversation discuss and practice greetings, responding to questions, asking questions, attending to the person, and saying good-bye. Have children role play a scene with the skill. Discuss possible things to say and do when having a conversation and how choices during a conversation affect the outcome of the interaction.

3. Bridge Home and School – Parents and teachers can work together to promote an interest in school friendships. Have children write a story about their classroom friends then ask parents to read and discuss the story at home. For younger children, include information about friends in notes home. Mention things like, “Alex played cars with Sarah in the sandbox.” Encourage parents to ask about who the child played with or worked with at school.

4. Activities Outside the Classroom - Children often see classmates at community activities. Joining a new activity with a classmate is a way to encourage friendships outside of school and have the support of an existing friend at a new event. Whether playing on a baseball team or attending story time, participating with someone the child knows is a way for them to have additional common interests.

5. Don’t Pressure Children – Teaching children the basics of being good to peers is important. Sometimes children develop close friendships this way, other times they will remain classmates. Do not force a friendship, but encourage children to share, say kind things, and be good to their classmates. Use children’s interests to involve them in activities such as sports, clubs, or neighborhood get-togethers they enjoy, so they continue to participate and find friends with similar hobbies.

Wednesday 17 August 2011

Six Tips for Making the Start of School Less Stressful

The beginning of the school year is an exciting time, but for many children getting backinto the routine can be difficult. Becoming familiar with new classrooms, classmates, rules, and teachers can be a difficult transition. Below are ideas for starting the new school year right.

1. Return to a School Sleep Schedule - Help children make the transition easier by getting them ready physically for early mornings. A gradual change is often more difficult than an immediate change. The first few days of getting up early and going to bed early may be difficult, but this will be helpful in the long run. Make getting up in the mornings easier by doing fun activities such as going on a walk, making breakfast together, or taking an early bike ride.

2. Introduce a New Environment or Re-Introduce a Familiar One: Three months goes by quickly, but children often forget many important things about school. Make a book with your child to remind them of their classmates’ names, teachers’ names, school layout (auditorium, art room, music room, etc.), bus rules, classroom rules, and school rules. Children can help by drawing pictures or writing the text. For children starting a new classroom or school, the teacher most likely will send information home that can be used to write a book.

3. Take Opportunities to Visit the School - Schools often have open houses or let children stop by before the year starts. A child’s stress can be reduced by seeing their classroom and meeting their teacher. If this is not possible, drive by the school and point out key areas such as the bus drop off/pick up, cafeteria, playground, auditorium, and gymnasium.

4. Involve Kids - Shopping for a book bag, new shoes, pencil holder, and other school necessities is a fun tradition for many families. Help your child write a list of items they need for school. Take the list to the store and let them pick out their own supplies. The list is a great way to practice reading and writing as well as planning. Give older children a budget to practice their math skills and to learn about decision making and purchasing.

5. Plan Ahead - Parents have many things to remember before the year starts. Make a list and check things off so your stress does not become your child’s stress. Scheduling medical appointments, buying school supplies, and figuring out the bus schedule in advance will make the days leading up to school more relaxed and less activity packed.

6. Create Summer Mementos – The end of summer can be very sad for many children. To remind them of the summer, have children create a collage of pictures, objects (e.g. event ticket stubs or magazine advertisements of movies or places they attended), or drawings. They also can make something for people they will miss. Have them write letters or make cards for people they will not see regularly during the school year such as camp counselors, camp friends, or lifeguards at the pool.

Saturday 6 August 2011

Maisie makes a splash!

Seven year old Maisie was so inspired by the courage of her friend, who is currently being supported by CLIC Sargent that she wanted to help.

Young Maisie joined in a Swim-a-thon at Yarborough swimming pool, and swam 21 lengths in 55 minutes as part of a relay team and raised a £20 for CLIC Sargent. Maisie was fantastic and star swimmer being the youngest in the team. All her team mates were over the age of 32!

Dad, Andrew also took part in the relay and said: “We are all extremely proud of Maisie and her fundraising; she was an inspiration to all the adults in the team.”

Well done Maisie!

People First Education are proud to support Clic Sargent. To find out more, click on there banner below right.

End of Summer Activities to Prepare for the School Year

The start of the school year is an exciting time but the transition back to school can be stressful for many children. Help children prepare for the new school year with these helpful strategies.

1. Review Skills and Goals – Review school reports and goals and document progress towards goals. If teachers and therapists provided activities or ideas to address skills, take the time to focus on these prior to school starting. Even small reminders about skills can help prepare children for addressing these in the classroom.

2. Take Advantage of Natural Learning Opportunities - Use natural opportunities to address a wide range of skills such as asking a child to help count silverware while setting the table (counting skills) or asking them to read directions while cooking (reading skills). By keeping a child’s goals top of mind, natural learning opportunities can be easily identified.

3. Use a Calendar for Visual Reminders – Many children benefit from visuals. Mark important events leading up to the start of school on the calendar. Examples of activities to put on the calendar are the first day of school, shopping for school clothes, and buying school materials. Discuss how many days are left until each event and have children participate in planning by helping write shopping lists and decide where to shop.

4. Return to a Schedule – Summer breaks often are not very structured. Start getting back into a routine so children are more prepared for the school year schedule. Sleeping, eating, brushing teeth, bathing, and bedtime rituals are examples of activities typically scheduled at set times in a child’s routine. Work on a consistent schedule to help transition back to school.

5. Use Art and Literature - Have children draw, make collages, or paint things they remember about the previous school year. Have them write about or discuss what things they like about school and what they are looking forward to in the new school year. Use these memories as visuals to discuss returning to school.

6. Play with Friends from School – Some children regularly see classmates over the summer while others only see school friends during the school year. Schedule play dates or host a classroom party to help children become re-acquainted with each other.

7. Enjoy the Rest of the Break – Although planning for the school year is important, make the most of the last few days of summer. Create lasting memories by going on picnics, attending community events, and taking advantage of extra family time. Take pictures to remind children of summer experiences and create a ‘Summer Memory’ book to encourage communication and language. This is a perfect item for show and tell at the start of the school year.

Wednesday 20 July 2011

Teaching Children to Practice Acts of Kindness

Being kind to other people and yourself is important for being a good friend and being happy. Modeling kindness, reflecting on kind actions, and practicing acts of kindness can help children develop this skill. This article includes strategies for helping children learn to be kind to other people and to themselves.

1. Be a Role Model – When adults say unkind things about other people or themselves, children learn this is acceptable behavior. Be a role model and say kind things about co-workers, neighbors, people in the community, and yourself.

2. Use Lists – Have children write lists or make collages representing what they like about their friends, family members, and people in the school. Hang the lists or art projects where classmates and friends can see them. Have a separate activity where children make a parallel list or art project that includes things they do well and why they are a good person.

3. Read and Write Stories – Read stories about kindness and respect in school and at home. Discuss how being kind makes the characters feel. Ask children to share times when they were kind and times when people were nice to them. Also have children write stories about being kind to other people.

4. Practice and Discuss Small Acts of Kindness – In addition to having children write and say things that are kind, have them practice little acts of kindness. Teach children to help other people in day to day situations such as when someone needs help carrying an item, they can’t reach something, or they drop an item. Create a set of pictures or make short stories with opportunities for small acts of kindness. Have children role play what they would do to be helpful in these situations.

5. Learning to Do Kind Things for Yourself – Have children write or create a collage about things they like to do or activities that make them feel good about themselves. Discuss how taking time to participate in these activities can make them feel better and decrease stress.

6. Pick a Cause or Charity – A long term investment in a volunteer or charity activity teaches children that even a small amount of time and energy makes a big difference. First create a list of volunteer opportunities then let the class or family select an activity to join. Whether it is collecting food for a food bank, donating toys, or cleaning up a community area, these activities demonstrate how working collaboratively with other people can make a big difference. Discuss or have children keep a journal about the experience. Ask them to include how they felt and how they think the people benefitting from their time and effort felt.

Tuesday 19 July 2011

Flint High School

Friday 15 July 2011

Wednesday 6 July 2011

How to Help Children Retain Skills over the Summer Holidays

Children often have a hard time retaining skills during the summer break. Many parents enroll children in summer school or extended school year, but this often is an abbreviated and less structured version of the school day. Even when children are educated at home, summer often involves routine changes. Since many children rely on consistent instruction, these changes can result in regression. This article includes strategies for preventing regression and teaching new skills.

1. Know What Skills to Work On - To prevent regression know what skills your child is working on and their current functioning level. Be sure to review their school progress reports, IEP (if applicable), and information from their teacher on summer reading and work. For children working on self-care, independence, or behavior skills, take data on their current progress. Be sure to ask their teachers and therapists what skills they are working on and exactly where they stand.

2. Find Opportunities to Practice Skills - Many skills can be integrated into a daily routine. Dressing, self-care, and behavior naturally occur during the day. Take time to use these natural occurrences as learning opportunities. For example, help your child as needed to put on their shoes rather than doing it for them. It may take longer for them to do the skill on their own, but it teaches them the steps they need to be more independent. Academic skills also can be integrated into a daily routine. Have children help with any math related problems and involve them in reading. For example, if you have a family picnic and 4 cousins, 3 aunts, 3 uncles, and 2 grandparents will be there, have your child help you count the number of cupcakes you need to bring. If you are baking the cupcakes, work on literacy skills by having your child read the recipe to you. Counting and fractions can be developed by gathering and measuring the ingredients. Children can work on motor skills by cutting butter, stirring ingredients, and pouring the batter into the tin. For children who need direct instruction, schedule a time during the day specifically to work on skills.

3. Build on Existing Skills - When children master a skill continue to review it, but also expand on skills. For example, if your child is mastering their current list of sight words, be sure to add additional words and phrases to their skill set. If they are able to count all the spoons the family has when helping to empty the dishwasher, add a serving spoon or two and teach them to count a little higher. Build on skills one step at a time so they are successful, enjoy learning, and do not become frustrated.

4. Appreciate Small Steps – It can be very frustrating for parents and professionals when children learn slowly or take a step backwards. Try to remember some skills take awhile for children to acquire. Sometimes children need additional examples of the skill or a new approach for instruction. Recognize that children become frustrated as well and teach them to be persistent and patient.

5. Realise It Is Summer – When children have different educational programs, therapies, and activities, it can be easy to forget summer break is also for relaxing. Although working on skills is important, be sure to enjoy the fun things summer has to offer. Enroll kids in swimming lessons, summer camp, tennis class, or just let them play outside. These kinds of activities are a way to stay healthy, learn new skills, and make new friends.

Thursday 30 June 2011

Children With Autism Face a Year Long Wait for Education Support

Actress Jane Asher with autistic pupil at Sybil Elgar School: 27 Per cent of survey spond Waited THEY Said Than Two more years for Appropriate Educational support. Image: NAS

By Janaki Mahadevan | Children & Young People Now

Almost half of all children with autism wait for More than a year for Appropriate Educational support, a report by the National Autistic Society (NAS) HAS found.

The Findings Accompany the launch of the charity's Great Expectations campaign, Aimed at Influencing Government Reform on Special Educational Needs (SEN) to Ensure the expectations of Both children and parents are met.

More than 1.000 parents of children with autism Were Surveyed by the society, with 48 per one hundred Saying THEY Waited More than a year to get the right support for Their 27 per child and one hundred WAS Saying the wait More than Two Years.

Eighteen per one hundred parents of Said THEY HAD taken legal action to get support for Appropriate and Their Children HAD gone to court year average of 3.5 times each.

Only 52 per one hundred of parents Said Their child WAS Making Good Educational Progress and seven out of 10 Did not Think It Had Been easy to get the education support Their child needed, while a further Top 47 per one hundred Said Their Child's Needs Were not Picked Up in Timely a way.

Mark Lever, NAS chief executive, said: "It Is Completely Unacceptable That So Many parents are still fighting a daily battle for Their Fundamental right to get education year for Their child. The government Rightly Recognise That Action Is Needed, and THEY That Need to Reform That system has continued to Many Children with autism let down.

"Our report sets out the Practical, Often simple steps That Can the government take to create a system That Works for everyone. Let's get it right. "

NAS Is Now That recommending Local Authorities work with schools and Other Services Such as to Ensure Health Have access to all schools and specialist support for chairs of governing bodies to Be Given Specific Training in SEN. According To the charity, health visitors and school staff must aussi Have Specific training in autism to Ensure THEY Can Identify early signs of the condition.

Referring to the new Health and Wellbeing boards, the report Said There Should Be more representation from schools. CYP Now Reported Earlier this month That initial research HAD Shown schools look Unlikely to Be Among the hand is on the boards.

NAS aussi wants Local Authorities to Increase transparency by publishing Their Strategic Plan for Children with SEN. The charity Said government must work with councils Also, parents and the Voluntary Sector to explore how Local Authorities Can Become parent champions.

Source: http://www.cypnow.co.uk/Health/article/1077097/Children-autism-face-year-long-wait-education-support

Sunday 26 June 2011

Thursday 23 June 2011

Strategies for Teaching Children to Make Good Choices

Choice is a big part of people’s lives. We decide daily what to wear, what to do, and how to treat people. Teaching children how to make good choices is critical for independence and self-control. This article focuses on a variety of strategies for teaching choice making.

1. Allow Children to Make Choices - Often it is easier to choose for children than allow them to decide for themselves. Unfortunately, lessons learned by making good and bad choices help children become responsible, independent adults. Choice also gives children a sense of ownership in activities. Take time to offer choices, create situations for choice, and reinforce the importance of good choices in your day.

2. Limit Choices - Keep the number and types of choices within reasonable limits. For example, if you let a child pick a snack, give them two or three healthy choices. By providing only allowable choices you reduce opportunities for conflict and create a situation where they succeed at making a good choice.

3. Discuss Options – When faced with decisions, think through and discuss the options to help children understand why one choice is better than another. Discuss possible choices, consequences, and why one option is better. For example, when leaving the house look outside and discuss the weather. Is it cold? Is it raining? Which coat is the better choice? What happens if you pick the light cotton coat and it rains? By guiding children through choices you teach them how to make decisions for themselves.

4. Consider Other People – When decisions involve other people, discuss the implications of the choice for the other people. For example, if a child wants to use the swing for the duration of recess discuss: Have other people asked to use the swing? Are other children waiting for the swing? How would you feel if you didn’t have a chance to use the swing? Are there other places you can play for part of recess? This helps children realize their choices affect people other than themselves.

6. Use Past Choices as Opportunities – When a child makes a bad choice such as cutting in line, saying something hurtful, or playing rather than finishing homework, use the opportunity to discuss why the choice was bad, consequences, and better choices for the future. Ask the child what other choices they could have made and what may have happened. Additionally, use past decisions and consequences as reminders. For example, “Noah, remember how you played video games rather than clean your room yesterday and had to miss your favorite show and clean up? What do you think you should do today?”

7. Praise Good Choices – When children make good decisions let them know what they did and why it was a good choice. For example, “Jason, I like the way you moved over to make room for Ella on the bus. It was nice of you to share your seat. That was a very good choice.”

8. State When There Is No Choice – Some situations such as safety and schedules have no choices. Holding hands crossing the street, participating in fire drills, and leaving on time for school are examples of times when there is no choice. Explain why these situations do not have choices and why all people must follow certain rules and schedules. Let children know if there is an aspect of the event that is their choice. For example, “We have to leave now for the bus, but you can carry your blue or red book bag.”

Wednesday 8 June 2011

Forthcoming Events

Social Story

15th June 2011 Wiltshire

17the June 2011 Cheltenham

20th June 2011 Sheffield

21st June 2011 Lancaster

22nd June 2011 Liverpool

23rd June 2011 Manchester

24th June 2011 Huddersfield

8th July 2011 Oxford

13th September 2011 Norfolk

20th September 2011 Gateshead

3rd October 2011 Peterlee

ADHD

27th June 2011 Welwyn Herts

14th September 2011 Burnley

15th September 2011 Bradford

16th September 2011 Birmingham

19th September 2011 Preston

21st September 2011 Sutton Colefield

29th September 2011 Derby

11th October 2011 Bristol

Autism Day Course

12th September 2011 Stevenage

23rd September 2011 Leeds

27th September 2011 Croydon

5th October 2011 Sevenoaks

15th June 2011 Wiltshire

17the June 2011 Cheltenham

20th June 2011 Sheffield

21st June 2011 Lancaster

22nd June 2011 Liverpool

23rd June 2011 Manchester

24th June 2011 Huddersfield

8th July 2011 Oxford

13th September 2011 Norfolk

20th September 2011 Gateshead

3rd October 2011 Peterlee

ADHD

27th June 2011 Welwyn Herts

14th September 2011 Burnley

15th September 2011 Bradford

16th September 2011 Birmingham

19th September 2011 Preston

21st September 2011 Sutton Colefield

29th September 2011 Derby

11th October 2011 Bristol

Autism Day Course

12th September 2011 Stevenage

23rd September 2011 Leeds

27th September 2011 Croydon

5th October 2011 Sevenoaks

Tuesday 7 June 2011

Helping Children Develop Friendships

Parents and professionals often struggle with helping children learn to be good friends or to understand the complexities of social interactions. Below are a number of strategies that can help children develop friendships.

1. Get Involved – Participate in community sports teams, art programs, and special events. These are wonderful opportunities for children to engage in structured activities with peers. For children with special needs, communities increasingly are offering camps and activities geared towards their specific needs. Ask professionals and support groups for information on these programs or check your community newspapers, centers, and websites. Another great activity, for children who benefit from very direct instruction, is social skills groups. These groups, which are offered in many communities, are a great way for children to develop their social skills in a fun yet structured environment.

2. Leverage the Child’s Interests – If the goal of enrolling a child in a program is to provide opportunities for making friends, look for activities the child enjoys. Some children like the arts while others enjoy sports. If a child is particularly shy, look for activities that initially have less direct contact. Tumbling and swimming are examples of individual sports while soccer and basketball involve more contact with peers. If children start in activities they enjoy, they are more likely to join other programs.

3. Role Play Difficult Skills – Practicing social skills is a way to work on specific aspects of social interactions. For example, if you notice your child stands too close to peers or repeatedly asks the same questions, help them learn about personal space or conversational skills through role play. By practicing these skills in the home, children can learn to improve their social skills and apply them outside the home.

4. Provide Examples – While reading books or watching television, explain social situations to children. Point out how helping others, using kind words, and listening when friends talk are ways to be a good friend. When characters are being hurtful or invading someone’s personal space, point these actions out and ask the child what the character could do differently to be a better friend.

5. Model Being Good to Others – Part of being well liked and being a good friend is being kind. Demonstrate kindness by saying nice things about and to others whether they are the grocery store employee or your neighbor. Point out when a co-worker does something thoughtful and how this makes you feel about them. If your child is sympathetic or says something complimentary, tell them their actions made you happy.

6. Do Not Force Friendships – Just like adults, children get along better with some peers than others. Teaching children to be kind and to include everyone in activities is important, but they do not have to be best friends with everyone.

Wednesday 25 May 2011

Ways to Increase Communication and Language

There are a variety of ways to increase communication depending on a child’s age and ability level. Below are some ideas for increasing language and communication throughout the day.

1. Expand Sentence Length – When children answer a question or request an item using one or two words, increase their sentence length by repeating their answer with an expanded phrase. For example, if you ask a child, “Would you like orange juice?” and they answer “Yes,” model a longer response. “Yes, I would like orange juice.” Then have the child repeat the phrase.

2. Use Books for Language - Reading stories is an excellent way to incorporate language into a fun activity. Ask questions about the pictures, the story, and the characters. Even very young children can identify colors, gender, words, or concepts (e.g. the boy that is the tallest/shortest) by pointing to pictures. Have children predict what is going to happen next throughout the story. After finishing the book, review what happened in the story.

3. Create Situations that Promote Language - Favorite toys, clothes, and foods can motivate young children to use language. Store favorite items in eye sight, but out of reach, so children have to use their words to request the items.

4. Provide Choices – Give children choices in activities, stories, toys, and foods so they communicate their preferences. You can create an opportunity for communication even if you know a child is going to select a favorite story or game.

5. Find Time to Communicate – Many children like being entertained by technology, but opportunities for communication are lost when families spend a good deal of time watching television and playing video games. Turn off the television during meals and refrain from using portable video games in the car. Time spent together at the dinner table and in the car are wonderful opportunities for learning about a child’s day and increasing communication and language skills.

6. Be Supportive – Children are more likely to communicate if they feel valued. Encourage language by listening attentively to children and asking them questions. If children answer questions incorrectly, teach them the correct answers using kind, supportive words. Repeatedly asking a question a child does not know how to answer or condescendingly correcting them can hurt their feelings and decreases the chance they will answer questions in the future. Instead, encourage them to say, “I don’t know,” and use the situation as a learning opportunity.

7. Be a Role Model – Children learn from the adults around them. When adults speak in full sentences, use correct grammar, and articulate well, children hear and are reminded of how words and sentences should sound.

Monday 23 May 2011

Online Dyspraxia Testing

Three of the team here at People First Education took an online Dyspraxia test today. Guess what... that's right, we were all diagnosed Dyspraxic and presented with a solution (which obviously had dollar signs attached) to our 'problem'.

Three comments:

1, None of these people have Dyspraxia, diagnosed or suspected.

2, This kind of test reduces the impact of genuine Dyspraxia.

3, How can we diagnose those we have not met?

Comment four:

This kind of website is a disgrace.

Remember Hill St Blues 'Be careful out there'

Developmental disability on rise in U.S. kids: Why?

Developmental disability is on the rise in the U.S. Between 1997 and 2008, the number of school-age children diagnosed with autism, ADHD, or another developmental disability rose by about 17 percent, a new study showed.

That means roughly 15 percent of kids - nearly 10 million - have such a disability.

The numbers were based on information collected from parents, who were asked whether their kids had been diagnosed with a variety of developmental disabilities, including cerebral palsy, seizures, stuttering or stammering, hearing loss, blindness, and learning disorders, as well as autism and ADHD.

Boys were twice as likely to have a developmental disability, according to the study, which was published in the June 2011 issue of Pediatrics. And except for autism, developmental disabilities were more common among children from low-income families.

"We don't know for sure why the increase happened," study author Sheree Boulet of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, told Reuters. There is now a bigger emphasis on early treatment, she said, and greater awareness about the conditions among parents.

But Philip Landrigan of the Mount Sinai School of Medicine in New York City, told USA Today that improvements in diagnosis can't fully explain the increase. Research suggests that environmental chemicals - including pesticides and the phthalates found in soft plastics - can affect kids' mental development, he said.

Whatever the cause of the increase, experts said the finding should remind parents to make sure their kids get screened. As Alison Schonwald of Children's Hospital Boston told USA Today, "It's great to diagnose them early, so we can intervene early and help them reach their full potential."

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has more on developmental disabilities.

Saturday 21 May 2011

Sunday 8 May 2011

A Hitchhikers Guide to Autism

Dear Friends and Colleagues,

After many months in the planning stages, the Autism training film 'A Hitchhikers Guide to Autism' is now coming to fruition. Filming took place last Thursday in the beautiful city of Lincoln in front of an invited audience of parents, professionals and students.

Everybody at People First Education would like to thank (in no particular order) the following individuals and organisations without whom this event could not have taken place:

Stuart McMorran from Fuse Design Ltd Nottingham

The Filming and Production Team at Blueprint Media

Vicky Fossett Illustrator and Artist

Matthew Pyburn ICT, Organisation and Logistics

Dr Claire Thomson from Bishop Grosseteste University College

Welton Kids Club

The Showroom Conference Centre Lincoln

and all those who attended the event

We now begin the lengthy task of post production and editing. It is hoped that the film will be available by September 2011

Tuesday 5 April 2011

Dunnitt

Dear Friends and Colleagues,